Alexander Kitaev was born in 1952 in Leningrad. Worked as a photographer at a shipbuilding enterprise (1978-1999). He received his primary photographic education at the VDK photo club and at the courses for photojournalists at the House of Journalists. Since 1975 he has been an active creative exhibition activities- Author of 35 solo and participant of more than 70 group exhibitions in Russia and abroad. Member of the Union of Photographers of Russia (1992). Member of the association “Photopostscriptum” (1993). Member of the Union of Artists of Russia (1994). The works are in Russian and foreign public and private collections. Currently works as a free-lance photographer.

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

1988

"City without kumach". showroom "Nevsky, 91", Leningrad

1991 "Playing with space". Design firm "Sosnovo", Leningrad.

1994

"A POSTERIORI". "PS-Place", St. Petersburg. (c)

"Constants". Exhibition Hall of the Moscow region. St. Petersburg (catalog)

"The tricks of Vertumnus". Studio "Stool", St. Petersburg

1995 "White Interior". "Golden Garden" Publishing house "LIMBUS-PRESS", St. Petersburg

1996 PHOTOSYNKYRIA 96. 9th International Meeting. Thessaloniki, Greece

"Petersburg Album". Gallery "Old Village", St. Petersburg

"Inside view" (FOTOFAIR'96) . Central Exhibition Hall "Manezh", St. Petersburg

"Petersburg through the eyes of Wubbo de Young, Amsterdam through the eyes of Alexander Kitaev." Nieuwe Kerk, Amsterdam; Central Exhibition Hall "Manege", St. Petersburg.

"Images of the Holy Mountain". KODAK Pro-Center, St. Petersburg.

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

1988 "...a city familiar to tears." Exhibition-action of the association "Community of Photographers", Leningrad - Moscow.

1989

"Weapon of Laughter" All-Union photo exhibition, Armavir (c)

IV Biennale of Analytical Photography. Yoshkar Ola, Cheboksary (c)

1993 "Annual Exhibition of the Union of Photographers of Russia". Central House of Artists, Moscow

"Photopostscriptum". Russian Museum, St. Petersburg (k)

1994-96 “Self-Identification. Aspects of St. Petersburg Art in the 1970s-1990s. Kiel, Berlin, Oslo, Sopot, St. Petersburg

1995 "The latest photography art from Russia". Frankfurt, Düsseldorf, Karlsruhe, Hannover, Gerten, Germany.

1997 "Petersburg' 96", Central Exhibition Hall "Manege", St. Petersburg

"Northern Dream" (CD-ROM Photo-show) within the framework of the festival "Salyut, Petersburg", World Financial Center, New York, USA

"Window to the Netherlands", Exhibition Center of the Union of Artists, St. Petersburg; Lily Zakirova Gallery, Hesden; showroom De Waag, Lesden; Conservatory of Groningen, Groningen;

“Photo relay race: from Rodchenko to the present day”, Municipal gallery “A-3”, Moscow;

"100 photographs of St. Petersburg", Biblioteka im. V.V. Mayakovsky, St. Petersburg; Russian Cultural Center, Prague;

Projectus. Thrown Forward”, Exhibition Center of the Union of Artists, St. Petersburg (catalogue);

New Photography from Russia, Gary Edwards Gallery, Washington, D.C., US;

“Exhibition of works by the folk photo studio “VDK”, Vyborg Palace of Culture, St. Petersburg;

"Shift. From Leningrad to Petersburg”, Museum of F. M. Dostoevsky, St. Petersburg;

Tower of Babel, Art College Gallery, St. Petersburg;

"Tara INCOGNITA", Museum of F. M. Dostoevsky, St. Petersburg

COLLECTIONS

State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

State Museum of the History of St. Petersburg, St. Petersburg

Museum of Photographic Collections, Moscow

The Gary Ranson Center for Humanitarian Researches, Austin, Texas, USA

The Navigator Foundation, Boston, USA

Mendl Kaszier Foundation, Antwerp, Belgium

Collection of the restaurant "Vena", St. Petersburg

Collection of the Free Culture Foundation, St. Petersburg

Collection of the publishing house "LIMBUS-PRESS", St. Petersburg

Bank Imperial, St. Petersburg

Paul Zimmer, Stuttgart, Germany

Herbrand, Cologne, Germany

and other private collections in Germany, Finland, Greece, the Netherlands, the USA and Russia.

Source http://www.photographer.ru/resources/names/photographers/26.htm

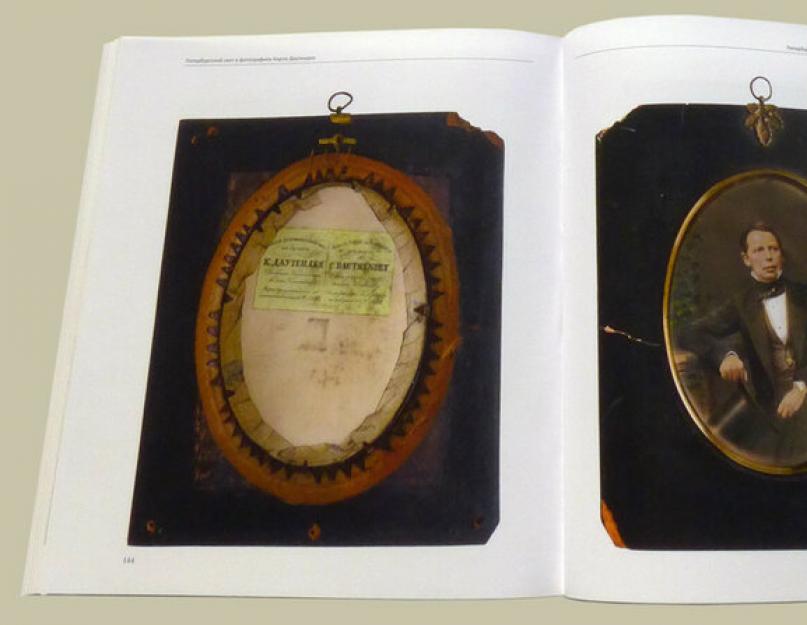

About the book by Alexander Kitaev "Petersburg light in the photographs of Karl Doutendey"

Dmitry Severyukhin

Alexander Kitaev

Petersburg light in the photographs of Carl Doutendey

St. Petersburg, "Rostok", 2016 - 204 p. (Series PHOTOROSSIKA)

ISBN 978-5-94668-188-9

For purchase and distribution inquiries, please contact:

[email protected],

[email protected];

www.rostokbooks.ru

The book by the well-known St. Petersburg photographer, curator, photography historian Alexander Kitaev tells about the different stages of the life and work of the outstanding photography pioneer Karl Doutendey, who created the first reliable photographic images of representatives of the highest strata of Russian society.

The book is addressed to a wide range of readers interested in the history of photography and the culture of St. Petersburg.

The name of the pioneer of photography, Karl Doutendey, is little known not only to the general public, but also to specialists, meanwhile, 19 years of his life and work were spent in the capital of the Russian Empire, and he stood at the very origins of domestic photography. Without going into listing the reasons for the current state of affairs, we note only one - for almost the entire 20th century, the state structure of Russia, to put it mildly, did not contribute to the study of pre-revolutionary culture, and, as a result, a huge layer of documents and materials on history domestic photography turned out to be little mastered and described. Until now, almost the only source of knowledge about the life and work of the photographer was the artistic autobiography of his son, the famous German artist and poet Max Doutendey, never published in Russian. And now, on 204 pages of the book by Alexander Kitaev, a well-known Russian photographer and historian of photography, for the first time we are reading a verified biography of the light painter, presented in detail and confirmed by documents. In addition, it reproduced more than 170 excellent rare photographic treasures provided by domestic and foreign government collections, as well as private collectors in Russia and Germany. Here the author published dozens of documents relating to the early period of Russian photography.

Full of ups and downs, the life of Karl Doutendey captures. He was born in tiny Saxon Aschersleben. In 1839, the year photography was born, he lost his father and trained as an optician-mechanic. In 1841, he bought a camera obscura in Leipzig and, having mastered the daguerreotype on his own, embarked on the path of a professional portrait painter full of commercial risks and competitive struggle. In 1843, the newly converted artist produced daguerreotype portraits of Duke Leopold of Dessaus and his family. In the same year, having secured a letter to the Russian Empress, the 24-year-old Saxon arrived in St. Petersburg. Soon he became one of the best daguerreotypers in the capital, and in 1847, before most of his colleagues, he finished with daguerreotype and switched to promising photographic technology according to the Talbot method. Making portraits of representatives of the upper strata of Russian society, by the beginning of the 1850s. master innovator took a leading position in the St. Petersburg photographic world. In the mid-1850s, after the invention of collodion technology and the total march of the so-called. "visiting cards", he was again on his own - he was the first in Russia to introduce photolithography, photograph the best representatives of Russian culture and distribute their portraits through magazines and art salons. In St. Petersburg, Doubenday was married twice. His first wife, having given birth to four daughters, committed suicide. The second wife, a Petersburger, bore him a son here. In 1862, family and business circumstances developed in such a way that the photographer was forced to leave Russia and settle in Bavaria, in Würzburg, where new ups and downs awaited him. Here, starting from scratch, calling himself "a photographer from St. Petersburg", he again became a leading portrait painter and a wealthy person. During the German period of his life, his second wife, who gave birth to another son, died of an incurable disease, his first-born son committed suicide, and younger son, flatly refusing to continue the work of his father, became, as already mentioned, a poet and artist.

Kitaev's book "Petersburg Light in the Photographs of Karl Doutendey" is more than just a biography of one of the first photographers who worked in the capital of Imperial Russia. The author, immersing the reader in the social atmosphere of Nikolaev and then post-reform St. Petersburg, tells in some detail about the beginnings of photography in Russia and Europe, shows both the professional environment of the master and the psychological environment in which the pioneers of photography had to operate. The book is written in plain language and beautifully illustrated with first-class artefacts from early photography.

The magnificent works of Carl Dauthendey have been in oblivion for more than 150 years and are now celebrating their real resurrection. The book by Alexander Kitaev sheds light not only on the amazing life and photographic heritage of the pioneer of photography, but makes it exciting interesting story cultures of the second half of the 19th century.

Dmitry Severyukhin,

doctor of art history, professor

They weren't bored

Commentary by Alexander Kitaev

From the day of its publication in 1839, light painting began to rapidly conquer the world. Photographers, being in a reckless and non-stop movement, either climbing rocky peaks or diving into the depths of the ocean, captured the globe in a historically short time, after which they rushed into the abyss of the universe and began to increasingly penetrate into the cosmos of human souls. Rebroadcast for more than two centuries in a row, the magazine and newspaper - "Photography has reached extraordinary perfection in our days" - is an unfading cliché of the headlines of reports about its military operations. This attack of photographers on all fronts, on all spheres of human activity, on the foundations of the universe that have developed over the centuries, was (and is) accompanied by continuous modernization and improvement of photographic tools, multiplying the arsenal of politicians and confessors, scientists and artists, warriors and civilians. However, even today, the beginning of this grandiose all-encompassing invasion remains poorly understood. Despite Benjamin's long-standing statement - "The fog that shrouds the origins of photography is still not so thick ..." - attempts to touch the spring remain completely rudimentary, and, as a result, today many avant-garde figures of the pioneers of photography are barely visible through the thickness of merciless years. There are many reasons for this, and it is not a trace to list them here, but it is important to note that the rejection of the technical nature of the new art played a bad joke on humanity: for more than a century, the most reliable refuge for incunabula early years the photographs remained only vulnerable filing cabinets and family albums. Of course, the impact of light painting was not as obvious and visible as the steam engine, construction railways, the introduction of electricity and aeronautics, but of all the technical innovations generated in the Iron Age and stunning contemporaries, only photography had a chance to acquire the status of another muse and join their round dance. But that didn't happen.

“Photography freed painting from boring work, above all from family portraits,” Auguste Renoir uttered, having made a career as a secular portrait painter. Just this, according to the eminent impressionist, a sad work, became the role of Doutendey and most of the first professionals in photography. They were not bored, and the “leaders of the sun” in just the first half century of the existence of photography filled family albums with as many impressions as all the renoirs of all countries of the world taken together would not have done. Millions of earthlings willingly appeared before their light-painting shells and preserved their authentic appearance for posterity. Meanwhile, the entry of the photographic portrait into everyday practice, into everyday life (the realm of elegance is a taboo!) was far from being peaceful and sometimes caused harsh rejection by many intellectuals. In the second half of the 19th century, “a new kind of painting” was vilified, humiliated, but there is not a single detractor who would not come to the photographer to take a portrait of himself, and then proudly send it to friends and relatives. And yet, since “people forced the sun – the beauty and driving force of the universe – to be a painter” (Bulgarin), from the arrogance of connoisseurs of beauty and petty-bourgeois neglect, a number of precious “pictures from nature” have disappeared. In a short period of time by historical standards, perhaps much more light-painted works were lost than any other cultural monuments from wars and revolutions, fires, floods and other natural and man-made disasters.

For me, there is no doubt that Carl Douthenday is one of the key figures in nineteenth-century photography, and the study of his life and professional path is essential for understanding the processes taking place at that time in society and in photography. The master stood at the origins of the now beloved kind of activity of the human race and lived together with photography, multiplying and improving it, for more than half a century. During the distance they traveled together, light painting evolved from a silver tablet on which Daguerre made a sunbeam capture the visible world, to the discovery by Doutendey's client Konrad Roentgen of unknown rays capable of drawing the invisible on a light-sensitive glass photographic plate. , and the survivors are quarreled over different countries. (The latter, however, is not depressing, because internationalism is a generic feature of photography.) In such a starting environment, work began on recreating the biography of the pioneer.

The pressure exerted by the practical Karl Dauthendey on his romantic offspring turned out to be so powerful that, accompanying the “prodigal son” on trips around the world, pursued him for many years. Perhaps the tension subsided only when the book “The Spirit of My Father” was published from the pen of the no longer young and famous writer Max Doutendey. In it, putting aside his favorite wandering rhymes, Maximilian clearly and talentedly retold his father’s stories he had heard since childhood about his first experiments in photography, the troubles he had experienced in Russia and his passionate but futile desire to transfer the work of his life into his son’s hands. In addition to this invaluable source, we owe the writer another treasure trove: having spent his life in continuous wandering, he somehow miraculously managed to save his father’s archive, part of which later ended up in the Würzburg municipal archive as part of the “Max Doutendey writer fund.”2 By the way, collections family photographic portraits during the earthly life of their first owners, as well as during the life of the first generation of heirs, did not arouse any public interest and carried the function of exclusively family memory. (And this is their difference from the pictorial portrait.) Only in the turbulent 20th century for Europe, with grandchildren and great-grandchildren, did many family archives involuntarily end up in museum collections, and then only as auxiliary utilitarian, illustrative material for various studies in the field of material culture.

And here it is impossible not to pay attention to the difference between the family album of a layman client and the photographer's own archive. And in both: dear people, but if in the first - completed and paid samples of someone else's work, then their author-performer is different. Every photographer knows that just pictures taken “for themselves” and “for their own”, and not for a capricious client, are the surest key to understanding the aspirations, searches and methods of work of a colleague. Who, if not the closest relatives and friends, can patiently endure the exercises of a light painter mastering innovations with due humility and understanding? Who, if not them, turning into resigned extras, become the first models of the artist seeking perfection, participants in his endless experiments, his risky experiments, during which, going into the unknown without fear of failure, the portrait painter can try new optics, test photographic materials, set dubious light , work out new poses, composition techniques, etc., etc.? Doubtenday, like many photographers of all future generations, honed his skills in photographing loved ones, and fortunately we had quite a few such photographs at our disposal. I should not fall into an art criticism analysis, and Doutenday never called himself an artist, but it is amazing how gracefully his pictures are built with his daughters, with sons, with other relatives, how accurate and unconstrained many single portraits of his performance - all these are signs not only high skill and a fairly developed sense of beauty, but also unconditional talent.

Without claiming to be a complete review of all the surviving works of Karl Dauthendey, the author set himself the task of identifying only photographs that reveal and explain the main stages professional activity masters and milestones of the formation of once new profession- a photographer. Whether it succeeded is for the reader to judge.

A. Kitaev

Source http://www.photographer.ru/events/review/6900.htm

Photos of Alexander Kitaev can be seen here

Shadogram, rayogram, photogram... This list can be continued by indicating one more name: Kitaev's photogram. In the late 1980s, or rather, in 1989, Alexander Kitaev “discovered” photography without a camera. It turned out that if the object is placed on photosensitive paper and a bright light is turned on, an unusual image will be obtained, only partly resembling the object itself. But if most of his famous predecessors worked with simple contours and silhouettes, then Alexander Kitaev began to experiment with volumetric glass and work with a beam of light like a brush. In his compositions, light becomes the main thing. Light creates a new reality that attracts the eye and invites you to travel in its depths, and objects acquire meaning and significance depending on how filled with light they are. And here you need a brilliant look of the artist, which,

as a "magic crystal", creates a magical "shift" in the perception of the world.

I.G.: Alexander, how did the photogram start for you? What prompted you to do this?

Alexander Kitaev: There were several messages for this. Let's start with what may seem at first glance rather prosaic. My favorite camera, with which I carried out my artistic gestures, began to die - all its vital organs began to fail under the influence of time. At that time I worked at the factory as a photographer, and I had plenty of any state-owned equipment, but for state-owned purposes I also worked with my camera, as it was much better: it gave a better image, there were better lenses, a better shutter, etc.

So, it was more and more difficult for the sick camera to work, and there was no opportunity to purchase a new instrument. My active creative life required finding an adequate outlet, and I decided to take photos without a camera.

Another reason that prompted me to take up photography was the desire to leave the utilitarian craft. I wanted abstract thinking and freedom from the actual photographic image.

I.G.: Were you familiar with similar images made by your predecessors? Did you try to imitate someone first, or did you immediately start doing something of your own?

Alexander Kitaev: When I became interested in photography, I became curious about who, when and how did this. So I learned that the first photographic images in Russia were "light pictures" - contact prints of plant leaves, obtained in the capital Petersburg by the botanist of the Imperial Academy of Sciences Yu. F. Fritsshe on light-sensitive materials made in 1839 by one of the fathers of light painting - Fox Talbot. In the 1920s, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, a representative of the famous Bauhaus art school, sought to create artistic images with the help of photography, and not documents, as was practiced in his time. In the same years, the world-famous Russian artist Alexander Rodchenko, whose photograms are quite rare in publications, and his contemporary, the creator of the Russian avant-garde Georgy Zimin, were engaged in photogramming, whose works are also difficult to see, since they are mostly in private foreign collections.

Of course, I tried to work with leaves, everyone tried it, and my first photograms were pretty simple. But I quickly realized that I was not interested in making a silhouette photogram, it was not interesting to build some recognizable images from these silhouettes (for example, portraits from paper clips). I wanted to completely "get rid" and make images of space and time without relying on the object and its obsessive outline.

For me, the photogram has replaced the still life, which I never did. I built compositions from transparent or translucent objects and tried to see their interaction with each other and with space.

I. G.: What feelings did you experience when you looked into a fantasy world through a bottle glass?

Alexander Kitaev: For me, it was an absolute passion, since my photogram images had no applied value, unlike the Bauhaus or Rodchenko, whose photograms were used in applied design to create covers, posters, etc. It was a game of freedom, I created space I felt like a demiurge.

Working with familiar objects, I saw how an essence invisible to us appears from them, how beautiful they are, how they want to be photographed (according to Baudrillard).

I.G.: How did your cycles develop, because these are not series, but cycles that can last indefinitely and gradually be supplemented?

Alexander Kitaev: That's why I called them cycles. I have to say, I didn't do it all the time. When immersed in the world of photograms for a month or

two, it was impossible to take a direct photo - I was all in this space. Then real life pulled me out of this state and forced me to take up applied photography again. I called the first formulated cycle “tare incognita” or, more simply, “unknown container” (1989-1990), in which I explored the plastic, light and shade, compositional and other possibilities of glass containers, then I just adjusted and looked closely at the objects.

In order to understand how to work with this or that vessel, at first I even started to make a gallery of portraits of bottles, their internal light appearance. The main thing was to choose the light and exposure in such a way that both the silhouette, and highlights, and internal structure object. Curious things came up. When the glare suddenly spills out of the object, you understand that the object lives not only in a closed space inside itself (a bottle, for example), but it also casts some kind of fluids, rays in all directions, which I tried to fix.

I.G.: Were there any favorite models?

Alexander Kitaev: Yes, I came across an object with which I worked for several years. He painted very beautifully inside himself, these rays lived their own lives, you could catch them in some fantastic combinations; it was a broken jug. When I left the factory, I was too lazy to pick it up: it seemed to me that this was a dead end, so much had already been done with it. But after a while I realized that I was sorely lacking him and there was no replacement for him.

I. G.: When you see an object, can you immediately assume what will come of it?

Alexander Kitaev: In different ways. Sometimes I feel what works and what doesn't. Sometimes the simplest and most unattractive bottles make wonderful images, but beautiful and elegant objects turn out to be uninteresting, or I just don’t know how to photograph them well.

I. G.: Have there been self-repetitions, and how difficult was it to avoid them?

Alexander Kitaev: The world of photo abstraction seemed endless to me, but, nevertheless, I saw my dead ends and tried to get away from the object. The photogram is always dictated by the scale of the object, the silhouette of a half-liter bottle fits on a 30x40 sheet. When I saw that the rays that I'm trying to save from it create a much larger image plane, I became interested in working further. Initially, my light source was an enlarger, later I began to build some installations that could allow me to transform an object and create much larger paintings from an object of the same scale. To do this, I used glass, mirrors. For example, meter-sized photograms were made from tiny cones that fit everything: their silhouettes, their shadows, their highlights. Then I came up with the idea of transforming the sheet of photosensitive paper itself to create another drawing. Application

toning and the use of different types of photo paper also gave additional options for creating unique images.

I.G.: Were your photogram cycles created one by one or did they overlap?

Alexander Kitaev: Of course, we crossed paths. For me it was pure play. I was always coming up with something new. For example, he began to create images by pouring developer onto sheets of light-sensitive materials.

Chemography - this is the name of this process - a very exciting activity! Almost in the same breath, I created photographic paintings, which subsequently formed two cycles: "The First Days of Creation" and "Listening to Music" (1990-1991). The "spree" in chemography lasted quite a long time and pushed the photogram a year and a half, until it appeared new idea. In those years, I bought a very expensive Russian-American album “Photographs of the Earth from Space”, which was very expensive at that time. I saw the Earth and realized that I see the same structures and textures in my glass objects. It was

insanely interesting, open space. This is how the cycles "The Forgotten Zodiac" and "Landscapes" (1994-1995) were born.

When I tried to change the light sources, to place them inside or at any point on the surface of the object, I again saw a striking

picture. I came across an object that, during such experiments, suddenly began to give some kind of physiological images with erotic overtones. These images formed another cycle, which I called "The Bottle Game" (1994).

There were also such photograms that were very fond of me, but did not fit directly into one or another cycle. And I came up with a name for them: "Journeys of Light." In fact, all photograms are journeys of light. This cycle is large enough and can be constantly supplemented.

I. G.: The photogram, with its unique aesthetics and limitless compositional possibilities, perhaps does not correspond to any

photography genre. Can it be attributed to a special kind of fine art?

Alexander Kitaev: Working with photograms, I studied the general laws of fine art, it was just more convenient for me to do it on photographic paper. What surprised me the most was that my attempts to practice new forms led to a change in the perception of the world and the creation of images that deviate far from photography. I liked the curious interpretation of the concepts of “light painting” and “photography” by V. T. Gruntal in the book “Photo illustration. Light painting. Transformation. Photomontage". Noting that the word "light painting" is the exact translation of the word "photography", the author did not put an equal sign between them, but argued that photography is only one of the special cases of light painting. Developing this idea, he wrote: “Obtaining an image with the help of light painting may not require optical systems necessary for photography. Having passed the centuries-old path, light painting is still applicable in its

pristine and pure, but already using the technical achievements that were made by the photography generated by it. Thus, according to Gruntal, everything that is written with the “pencil of nature”, as Talbot designated his invention, in time immemorial was divided into two areas: light painting as a pure art and photography as an applied skill.

I. G.: Your photograms invariably evoke a wide range of emotions from misunderstanding and even rejection to complete delight. Is it possible to

how to help the incomprehensible viewer and is it necessary to do this?

Alexander Kitaev: Every person is endowed with the ability to perceive, but not everyone has developed a skill out of this ability. Bringing some kind of literature into abstract compositions (for this it is enough to title only the cycles, and not each image separately), it is not at all necessary to force the viewer to read this literature. It is much more valuable to give freedom to read an artistic statement.

I.G.: Despite the fact that the photogram remains rare and exotic today, the hobby of a few lovers of random, unpredictable

games are, fortunately, connoisseurs of such creativity. Is it a pity to part with a unique work that has no circulation?

Alexander Kitaev: If I publish my work, it already lives its own independent life, and its life is much longer than mine. If appreciated and purchased - it's nice.

Photographer, curator, photography historian. Born in 1952 in Leningrad. Member of the Union of Photographers of Russia (1992), the Union of Artists of Russia (1994). In 1977 he graduated from the Faculty of Photojournalism of the City University of Workers' Correspondents at the Leningrad House of Journalists. He was a member of amateur photography associations: photo clubs of the VDK, Druzhba (1972-1982); "Mirror" (1987-1988). Worked as a photographer at a shipbuilding enterprise (1978-1999). Member of the organizational board of the festival "Traditional Autumn Photo Marathon" (1998-2003). Since 1999 freelance artist. In 2000, he organized the Art-Tema publishing house, which specialized in publishing publications on photography (art director, 2000-2001). Editor of the "Art Attic" section of the network magazine Peter-club (2000-2001). Art director of the Raskolnikov photo gallery (2004-2005). Author of more than seventy solo exhibitions held in Russia, England, Germany, Holland, Greece, Italy, Switzerland, participant of more than 150 group exhibitions. From 1996 to 2010 as a curator, he carried out eighteen exhibition projects. Author of texts on the history of photography, author and compiler of a number of albums and books. Scholarship holder of the Paris City Hall (2006).

The works are stored in the State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg; Russian National Library, St. Petersburg; State Museum of the History of St. Petersburg; Yaroslavl Art Museum; Museum "Moscow House of Photography"; Moscow Museum of Modern Art; State Russian Museum of Photography, Nizhny Novgorod; Museum of Photographic Collections, Moscow; Museum of Nonconformist Art, St. Petersburg; State Center photographs (ROSPHOTO), St. Petersburg; Photographic Museum "Metenkov's House", Yekaterinburg; Literary and Memorial Museum of F.M. Dostoevsky, St. Petersburg; Museum of the Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkin House), St. Petersburg; St. Petersburg State Museum of Musical and Theatrical Art, St. Petersburg; Museum "House of V. V. Nabokov", St. Petersburg. The works are included in the collections of: Free Culture Foundation, St. Petersburg; Foundation historical photography them. Karl Bulla, St. Petersburg; Ruarts Foundation, Moscow; Museum of the History of Photography, St. Petersburg; Museum of Organic Culture, Kolomna; Lumiere Brothers Center for Photography, Moscow; Harry Ranson Humanitarian Research Center, Austin, Texas, USA; E. Yu. Andreeva, St. Petersburg; V. N. Valrana, St. Petersburg; Galleries "Artnasos", St. Petersburg; Galleries Gisich, St. Petersburg; M. I. Golosovsky, Krasnogorsk; A. V. Loginova, Moscow; O. I. Plyushkova, St. Petersburg; Luke & A Gallery of Modern Art, London; The Navigator Foundation, Boston, USA; The Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection, USA; The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers; The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswik, NJ, USA; Mendi Kaszier Foundation, Antwerpen, Belgien; Jean Olaniszyn Collection, Losone, Svizzera; M. Redaelli & P. Todorovch, Sorengo, Svizzera; Russian Art Collection Gianni Foraboschi, Milano, Italia; Mark Faist, Houston, TX, USA; cultural center Locarno "Rivellino LDV", Svizzera and others.

He lectured on the history and theory of photography and held master classes at the State Museum of the History of St. Petersburg; State Russian Museum of Photography (Nizhny Novgorod); Photographic Museum "Metenkov's House" (Yekaterinburg); Youth Educational Center of the State Hermitage; Museum of the History of Photography (St. Petersburg); Museum of the History of Photography (Kolomna); Baltic Photo School (St. Petersburg); Foundation "Petersburg Photo Workshops" (St. Petersburg); School of Visual Arts (Moscow); Kaliningrad Union of Photographers; State Center for Photography ROSPHOTO (St. Petersburg); Leica Akademie (Moscow), etc.

Op.:

Blessing / int. Art. I. Chmyreva. SPb., 2000

Involuntary landscape line / int. Art. V. Savchuk. SPb., 2000

Still-light / int. Art. I. Chmyreva. SPb., 2000

Photographic time of Karl Bulla / Petersburg. 1903 in photographs by K.K. Bulls: catalogue, 2003

Vasily Sokornov. Specialty: views of the Crimea / Vasily Sokornov. Types of Crimea: catalogue. SPb., 2005

Living beings in light-painting representation / Dots. On the history of photography. Album. SPb., 2005

The first light painter of St. Petersburg / Ivan Bianchi - the first light painter of St. Petersburg: catalogue. SPb., 2005

Life-affirming genre / Nu. Album. SPb., 2006

Subject. Photographer about photography. SPb., 2006

About photography, Petersburg and the end of the century / Boris Smelov. Retrospective: GE catalogue, 2009

Genre: Petersburg. Album. SPb., 2011

Subjectively about photographers. Letters. St. Petersburg, 2013

Petersburg Expedition of Ivan Bianchi / Russian World: Almanac. St. Petersburg, 2014

St. Petersburg in the works of German photographers of the 19th century: catalogue. St. Petersburg, 2014

Petersburg Ivan Bianchi. Post restante. St. Petersburg, 2015

Lit.:

Photopostscriptum: catalog / int. Art. A. Borovsky, St. Petersburg, 1993

Self-Identification. Positions in St. Petersburg Art from 1970 to Today. Berlin, 1994

Die neue russische Fotografie: Catalogue. Leverkusen, Germany, 1998

The Russian Museum presents: Abstraction in Russia. XX century / Almanac. Issue. 17. Timing. St. Petersburg, 2001

Savchuk V. Conversion of art. SPb., 2001

Photography of the posterotic era / Ontology of possible worlds / materials scientific conference under. ed. B.I. Lipsky. SPb., 2001

Black & White Petersburg 1703-2003: Catalogue. St. Petersburg, 2002

The Nude in the post-erotic Age. Das rigorose Gluck. Erste Annaerung. Hrg. Bernd Ternes und dem RG-Verein. Marburg, 2002

St. Petersburg in Black-and-White. State Russian Museum, Palace Editions, 2003

Valran V.N. Leningrad underground: painting, photography, rock music. SPb., 2003

Two waters. Saint Petersburg. Album. SPb., 2003

The Russian Museum presents: Black and White Petersburg / Almanac. Issue. 45. Timing. St. Petersburg, 2003

The Russian Museum presents: Emperor Paul I. The current image of the past / Almanac. Issue. 100. Timing. SPb., 2004

Savchuk V. Philosophy of photography. SPb., 2005

Stigneev V. T. Age of photography. 1894-1994. Essays on the history of Russian photography. M., 2005

Outcrop. New Russian photography. Album. Wedge, 2006

Photo relay from Rodchenko to the present day. Pages of the history of Soviet and modern Russian photography. M., 2006

Podolsky N. Homo photos. Alexander Kitaev / Behind the lens. Essays about Petersburg photographers and photography. SPb.-M, 2008

Outpost. Photo album. M, 2012

Fotofest 2012 biennial. fine print auction. Houston, Texas, USA

Podolsky N. The artist's gene in photographic reality. Essay on artistic photography. St. Petersburg, 2013

Vasiliev S. Vocation-photographer. Chelyabinsk, 2014

Fine Arts of St. Petersburg. M, 2014

November 18th The School of Visual Arts (Moscow) invites you to an exclusive lecture by the famous photographer, curator, historian of photography Alexander Kitaev as part of the School's new rubric #PITERFOTOFEST-2018. continuation*.

The topic of Alexander Kitaev's lecture: “PHOTOMANIA. A shift from a fashionable living room to a raznochintsy shelter.

Start at 15. 00

We will learn about the photographic pandemic that literally engulfed all of humanity in the first century of the invention of photography and understand the literal meaning of the words: "photomania", "cartomania", "album mania", we will be surprised that, it would seem, the product of the 21st century "no photography - no man or events” goes back to the 19th century.

Alexander Kitaev: “Light painting, which showed great promise of becoming a new art, humbled its ambitions from the fifties of the 19th century and, having taken up the service of everyday needs of commoners, firmly established itself in the rank of craft. Next to the representative of the church who had consecrated family rites from time immemorial, a new actor- The photographer who covered these events. The sacraments of the church rite and the mysterious light-painting image merged in the family album, laying the foundation for building their own family tree tradition, similar to the genealogical tree that was previously considered the exclusive privilege of the nobility. In the same place, as proof of their involvement in the political and public life of countries, along with photographs illustrating the stages of family life, portraits of celebrities began to coexist. This phenomenon in the history of photography was called "cartomania" or, in other words, "album mania". What, however, does not change the essence - the passionate collecting of photographic cards and placing them in home albums has acquired the character of a pandemic.